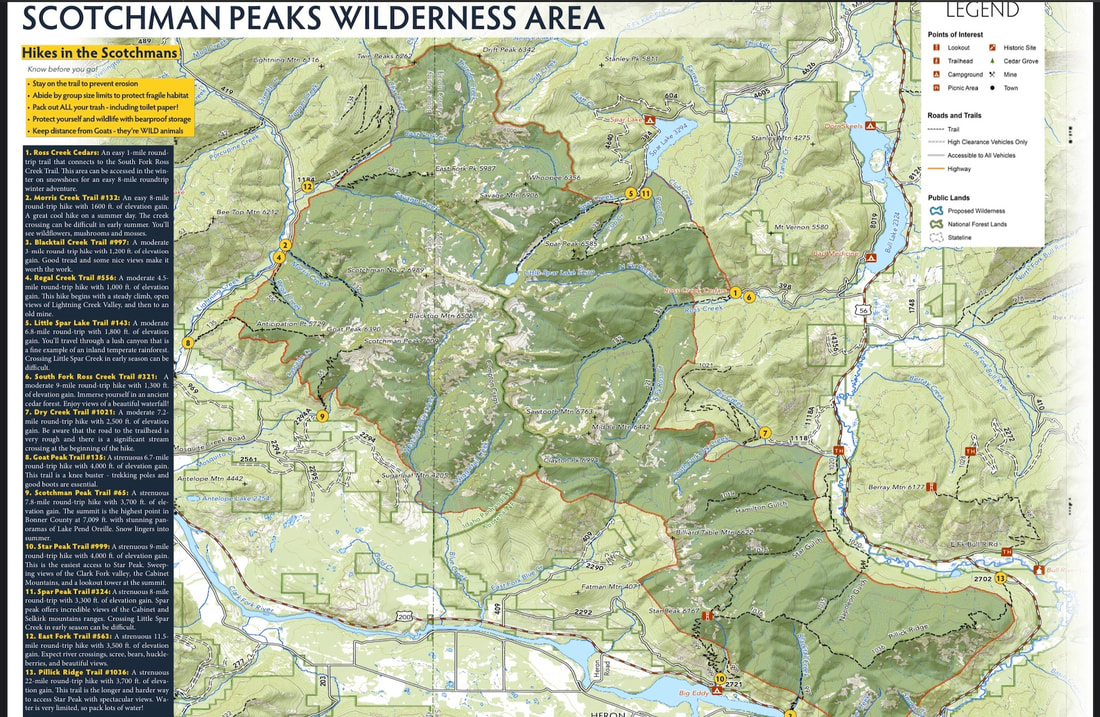

THIS MAP IS COURTESY OF THE PROPOSED SCOTCHMAN PEAKS WILDERNESS

Friends of Scotchman Peaks Wilderness Mission, Vision and History

Mission: To protect the Scotchman Peaks for future generations through Wilderness designation, ongoing stewardship and education.

Vision: We are uniting thousands of Montanans and Idahoans to save the wild Scotchmans for our children and grandchildren.

History: The Scotchman Peaks roadless area is one of largest and wildest roadless areas in the region. Roughly 60 miles south of Canada, it spans the Idaho and Montana border. It covers parts of two national forests (Idaho Panhandle and Kootenai). And three counties (Bonner, Sanders, Lincoln.)

The Scotchman Peaks have been recognized for their Wilderness value since the RARE processes in the 1970s. Forest plan revisions in 2002 were not giving enough attention to that value. People from all walks of life came together in 2005 to be a voice for the Scotchmans. In 2015, the final forest plans had most of the Scotchman Peaks as recommended Wilderness.

FSPW has been signing people up as “Friends of the Scotchman Peaks” since formation in 2005.

In the past 16 years, over 9,000 people have signed on to say they support saving the wild Scotchmans. The majority live within 100 miles of the Scotchmans. We are building the local grassroots support needed for congress to act. And the local support to take care of the land before and after it becomes a Wilderness area.

Scotchman Peaks

The Landscape

A little-known chunk of wild country occupies a place in the Cabinet Mountains where the Idaho-Montana state line slices through the mountains north of the Clark Fork River. Bounded by Lightning Creek in Idaho and Bull River in Montana, the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area is comprised of 88,000 acres of undeveloped public lands managed by the Idaho Panhandle National Forests and the Kootenai National Forest. Much of this rugged landscape is as inaccessible now as it was almost 200 years ago when David Thompson explored the Clark Fork River and established a trading post at nearby Lake Pend Oreille.

Among the reasons why the area remains so wild is the ruggedness that characterizes so much of its terrain. Crowned by Scotchman Peak at 7,009 feet, the highest point in Bonner County, Idaho, the heart of the Scotchmans is defined by two sheer ridgelines separating Lightning Creek from Blue Creek and Blue Creek from Ross Creek, the primary drainages bisecting these mountains. This remote high country boasts glacially carved basins with exposed sedimentary rock hundreds of millions of years old.

More than 40 streams from Mink Creek to Gin Gulch tumble off two-dozen named peaks stretching from Lightning Mountain to Pillick Ridge. A great deal of water is shed by the Scotchmans, yet despite the liquid abundance, there are only three or four lakes within the roadless area, and only one of those has a name: Little Spar Lake.

The water flowing from the Scotchmans goes in two directions, but ultimately ends up in the same place. Ross Creek, Spar Creek and Keeler Creek with their tributaries all flow into Lake Creek, which meanders north from Bull Lake to the Kootenai River. Bull River, Blue Creek and Lightning Creek, with their 30 or more tributaries, flow into the Clark Fork River, which empties into Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho’s largest lake.

Several small communities are located in the vicinity of the Scotchmans. Clark Fork, Idaho, is situated at the confluence of Lightning Creek with the Clark Fork River; Heron, Montana, is on the south bank of the Clark Fork about halfway between Blue Creek and Bull River; Noxon, Montana, is five miles southeast of Bull River; and Troy, Montana, is a dozen miles north of Bull Lake where Lake Creek joins the Kootenai. Access to the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area begins in these communities. Highway 200 parallels the southern edge through Idaho and Montana. At Clark Fork, Idaho, Lightning Creek Road No. 419 follows Lightning Creek all the way to Rattle Creek. Here a U.S. Forest Service Road climbs over Rattle Pass and descends Keeler Creek, eventually joining Lake Creek Road No. 384, which exits the mountains to Troy, Montana, and Highway 2. Highway 2 is connected with Highway 200 in Montana by way of Highway 56, commonly called the Bull River Highway, which is often lauded as the most scenic drive in western Montana. From this road there is vehicle access to Spar Lake and the Ross Creek Cedars.

A small but well-maintained trail system provides exceptional hiking opportunities into the Scotchmans. The most heavily used trails go to Little Spar Lake, Scotchman Peak and Star Peak, where an active forest fire lookout tower is manned during the summer months. Approximately 50 to 60 miles of foot trails probe the backcountry of the Scotchman Peaks.

Geology, Ice and Water

The Scotchman Peaks are an historic mountain range. David Thompson saw them much as they are today when he passed this way in 1809. But travel further back in time – like say 12,000 years – and you would not have recognized this place. It was covered in ice and water. Glacial Lake Missoula, that gargantuan body of water that contained more liquid than all the rivers of the world today, lapped at icy shorelines more than halfway up the sides of Star Peak and Clayton Peak, and totally submerged Fatman Mountain. Arctic conditions ruled the landscape in those days.

But go further back in time still, through thousands of centuries and hundreds of millennia, and you will enter a region covered by a vast sea. The Scotchmans, as is most of the Cabinet Mountain Range, is sedimentary in origin, which means the layers of mud and silt and sand that mark each horizon of rock were laid down over countless millions of years by the simple mechanics of erosion and deposition. And then the earth trembled, buckled and moved, heaving upward into the sky, and the sea vanished. The mountains were born, a rugged range of fractured slabs of lake bottom silts metamorphosed into rock.

When these mountains were already ancient, another period of violent activity within the earth’s crust pushed sills of granite and diorite into the spaces between the sedimentary layers. This was up to135 million years ago. To the west, the Selkirk Mountains came into being, but in the Cabinets and the Scotchmans, the granite surfaced only in a few places. Broken, angular, ragged, rotten sediments passing for rock still dominate today the makeup of these mountains. As Nan Compton says, after having seen a video of the Scotchmans taken from a plane, “I had no idea the area was so rugged and wild. From Little Spar Lake to Scotchman No. 2 is one huge mass of cirques and slide areas, boulders bigger than houses, mountain meadows and animal trails. Sawtooth sticks up like a huge nose with Middle Mountain between it and Clayton Peak.”

The continental ice sheet from the north did its best to soften the edges of the Scotchmans, but the massive glacier’s leading edge halted its southern progress at the mouth of what we now call the Clark Fork River and created an ice dam more than 2,000 feet thick. This is what created Lake Missoula, a lake that ate away at the edges of the ice from Pillick Ridge to the Missions, the Rattlesnake and the Sapphires. And it ate away at the ice dam itself so that finally, and maybe many times over, the dam collapsed and the lake catastrophically drained into Idaho and Washington, carrying Montana sediment and boulders all the way to Oregon.

The Scotchmans, site of the wondrous ice dam that created such havoc to so much of the Inland Northwest, watched all this happen, then spent the next 10,000 years evolving the forests and wildlife found there today.

Scotchman Peaks The Landscape

A little-known chunk of wild country occupies a place in the Cabinet Mountains where the Idaho-Montana state line slices through the mountains north of the Clark Fork River. Bounded by Lightning Creek in Idaho and Bull River in Montana, the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area is comprised of 88,000 acres of undeveloped public lands managed by the Idaho Panhandle National Forests and the Kootenai National Forest. Much of this rugged landscape is as inaccessible now as it was almost 200 years ago when David Thompson explored the Clark Fork River and established a trading post at nearby Lake Pend Oreille.

Among the reasons why the area remains so wild is the ruggedness that characterizes so much of its terrain. Crowned by Scotchman Peak at 7,009 feet, the highest point in Bonner County, Idaho, the heart of the Scotchmans is defined by two sheer ridgelines separating Lightning Creek from Blue Creek and Blue Creek from Ross Creek, the primary drainages bisecting these mountains. This remote high country boasts glacially carved basins with exposed sedimentary rock hundreds of millions of years old.

More than 40 streams from Mink Creek to Gin Gulch tumble off two-dozen named peaks stretching from Lightning Mountain to Pillick Ridge. A great deal of water is shed by the Scotchmans, yet despite the liquid abundance, there are only three or four lakes within the roadless area, and only one of those has a name: Little Spar Lake.

The water flowing from the Scotchmans goes in two directions, but ultimately ends up in the same place. Ross Creek, Spar Creek and Keeler Creek with their tributaries all flow into Lake Creek, which meanders north from Bull Lake to the Kootenai River. Bull River, Blue Creek and Lightning Creek, with their 30 or more tributaries, flow into the Clark Fork River, which empties into Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho’s largest lake.

Several small communities are located in the vicinity of the Scotchmans. Clark Fork, Idaho, is situated at the confluence of Lightning Creek with the Clark Fork River; Heron, Montana, is on the south bank of the Clark Fork about halfway between Blue Creek and Bull River; Noxon, Montana, is five miles southeast of Bull River; and Troy, Montana, is a dozen miles north of Bull Lake where Lake Creek joins the Kootenai. Access to the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area begins in these communities. Highway 200 parallels the southern edge through Idaho and Montana. At Clark Fork, Idaho, Lightning Creek Road No. 419 follows Lightning Creek all the way to Rattle Creek. Here a U.S. Forest Service Road climbs over Rattle Pass and descends Keeler Creek, eventually joining Lake Creek Road No. 384, which exits the mountains to Troy, Montana, and Highway 2. Highway 2 is connected with Highway 200 in Montana by way of Highway 56, commonly called the Bull River Highway, which is often lauded as the most scenic drive in western Montana. From this road there is vehicle access to Spar Lake and the Ross Creek Cedars.

A small but well-maintained trail system provides exceptional hiking opportunities into the Scotchmans. The most heavily used trails go to Little Spar Lake, Scotchman Peak and Star Peak, where an active forest fire lookout tower is manned during the summer months. Approximately 50 to 60 miles of foot trails probe the backcountry of the Scotchman Peaks.

Geology, Ice and Water

The Scotchman Peaks are an historic mountain range. David Thompson saw them much as they are today when he passed this way in 1809. But travel further back in time – like say 12,000 years – and you would not have recognized this place. It was covered in ice and water. Glacial Lake Missoula, that gargantuan body of water that contained more liquid than all the rivers of the world today, lapped at icy shorelines more than halfway up the sides of Star Peak and Clayton Peak, and totally submerged Fatman Mountain. Arctic conditions ruled the landscape in those days.

But go further back in time still, through thousands of centuries and hundreds of millennia, and you will enter a region covered by a vast sea. The Scotchmans, as is most of the Cabinet Mountain Range, is sedimentary in origin, which means the layers of mud and silt and sand that mark each horizon of rock were laid down over countless millions of years by the simple mechanics of erosion and deposition. And then the earth trembled, buckled and moved, heaving upward into the sky, and the sea vanished. The mountains were born, a rugged range of fractured slabs of lake bottom silts metamorphosed into rock.

When these mountains were already ancient, another period of violent activity within the earth’s crust pushed sills of granite and diorite into the spaces between the sedimentary layers. This was up to135 million years ago. To the west, the Selkirk Mountains came into being, but in the Cabinets and the Scotchmans, the granite surfaced only in a few places. Broken, angular, ragged, rotten sediments passing for rock still dominate today the makeup of these mountains. As Nan Compton says, after having seen a video of the Scotchmans taken from a plane, “I had no idea the area was so rugged and wild. From Little Spar Lake to Scotchman No. 2 is one huge mass of cirques and slide areas, boulders bigger than houses, mountain meadows and animal trails. Sawtooth sticks up like a huge nose with Middle Mountain between it and Clayton Peak.”

The continental ice sheet from the north did its best to soften the edges of the Scotchmans, but the massive glacier’s leading edge halted its southern progress at the mouth of what we now call the Clark Fork River and created an ice dam more than 2,000 feet thick. This is what created Lake Missoula, a lake that ate away at the edges of the ice from Pillick Ridge to the Missions, the Rattlesnake and the Sapphires. And it ate away at the ice dam itself so that finally, and maybe many times over, the dam collapsed and the lake catastrophically drained into Idaho and Washington, carrying Montana sediment and boulders all the way to Oregon.

The Scotchmans, site of the wondrous ice dam that created such havoc to so much of the Inland Northwest, watched all this happen, then spent the next 10,000 years evolving the forests and wildlife found there today.

Mission: To protect the Scotchman Peaks for future generations through Wilderness designation, ongoing stewardship and education.

Vision: We are uniting thousands of Montanans and Idahoans to save the wild Scotchmans for our children and grandchildren.

History: The Scotchman Peaks roadless area is one of largest and wildest roadless areas in the region. Roughly 60 miles south of Canada, it spans the Idaho and Montana border. It covers parts of two national forests (Idaho Panhandle and Kootenai). And three counties (Bonner, Sanders, Lincoln.)

The Scotchman Peaks have been recognized for their Wilderness value since the RARE processes in the 1970s. Forest plan revisions in 2002 were not giving enough attention to that value. People from all walks of life came together in 2005 to be a voice for the Scotchmans. In 2015, the final forest plans had most of the Scotchman Peaks as recommended Wilderness.

FSPW has been signing people up as “Friends of the Scotchman Peaks” since formation in 2005.

In the past 16 years, over 9,000 people have signed on to say they support saving the wild Scotchmans. The majority live within 100 miles of the Scotchmans. We are building the local grassroots support needed for congress to act. And the local support to take care of the land before and after it becomes a Wilderness area.

Scotchman Peaks

The Landscape

A little-known chunk of wild country occupies a place in the Cabinet Mountains where the Idaho-Montana state line slices through the mountains north of the Clark Fork River. Bounded by Lightning Creek in Idaho and Bull River in Montana, the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area is comprised of 88,000 acres of undeveloped public lands managed by the Idaho Panhandle National Forests and the Kootenai National Forest. Much of this rugged landscape is as inaccessible now as it was almost 200 years ago when David Thompson explored the Clark Fork River and established a trading post at nearby Lake Pend Oreille.

Among the reasons why the area remains so wild is the ruggedness that characterizes so much of its terrain. Crowned by Scotchman Peak at 7,009 feet, the highest point in Bonner County, Idaho, the heart of the Scotchmans is defined by two sheer ridgelines separating Lightning Creek from Blue Creek and Blue Creek from Ross Creek, the primary drainages bisecting these mountains. This remote high country boasts glacially carved basins with exposed sedimentary rock hundreds of millions of years old.

More than 40 streams from Mink Creek to Gin Gulch tumble off two-dozen named peaks stretching from Lightning Mountain to Pillick Ridge. A great deal of water is shed by the Scotchmans, yet despite the liquid abundance, there are only three or four lakes within the roadless area, and only one of those has a name: Little Spar Lake.

The water flowing from the Scotchmans goes in two directions, but ultimately ends up in the same place. Ross Creek, Spar Creek and Keeler Creek with their tributaries all flow into Lake Creek, which meanders north from Bull Lake to the Kootenai River. Bull River, Blue Creek and Lightning Creek, with their 30 or more tributaries, flow into the Clark Fork River, which empties into Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho’s largest lake.

Several small communities are located in the vicinity of the Scotchmans. Clark Fork, Idaho, is situated at the confluence of Lightning Creek with the Clark Fork River; Heron, Montana, is on the south bank of the Clark Fork about halfway between Blue Creek and Bull River; Noxon, Montana, is five miles southeast of Bull River; and Troy, Montana, is a dozen miles north of Bull Lake where Lake Creek joins the Kootenai. Access to the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area begins in these communities. Highway 200 parallels the southern edge through Idaho and Montana. At Clark Fork, Idaho, Lightning Creek Road No. 419 follows Lightning Creek all the way to Rattle Creek. Here a U.S. Forest Service Road climbs over Rattle Pass and descends Keeler Creek, eventually joining Lake Creek Road No. 384, which exits the mountains to Troy, Montana, and Highway 2. Highway 2 is connected with Highway 200 in Montana by way of Highway 56, commonly called the Bull River Highway, which is often lauded as the most scenic drive in western Montana. From this road there is vehicle access to Spar Lake and the Ross Creek Cedars.

A small but well-maintained trail system provides exceptional hiking opportunities into the Scotchmans. The most heavily used trails go to Little Spar Lake, Scotchman Peak and Star Peak, where an active forest fire lookout tower is manned during the summer months. Approximately 50 to 60 miles of foot trails probe the backcountry of the Scotchman Peaks.

Geology, Ice and Water

The Scotchman Peaks are an historic mountain range. David Thompson saw them much as they are today when he passed this way in 1809. But travel further back in time – like say 12,000 years – and you would not have recognized this place. It was covered in ice and water. Glacial Lake Missoula, that gargantuan body of water that contained more liquid than all the rivers of the world today, lapped at icy shorelines more than halfway up the sides of Star Peak and Clayton Peak, and totally submerged Fatman Mountain. Arctic conditions ruled the landscape in those days.

But go further back in time still, through thousands of centuries and hundreds of millennia, and you will enter a region covered by a vast sea. The Scotchmans, as is most of the Cabinet Mountain Range, is sedimentary in origin, which means the layers of mud and silt and sand that mark each horizon of rock were laid down over countless millions of years by the simple mechanics of erosion and deposition. And then the earth trembled, buckled and moved, heaving upward into the sky, and the sea vanished. The mountains were born, a rugged range of fractured slabs of lake bottom silts metamorphosed into rock.

When these mountains were already ancient, another period of violent activity within the earth’s crust pushed sills of granite and diorite into the spaces between the sedimentary layers. This was up to135 million years ago. To the west, the Selkirk Mountains came into being, but in the Cabinets and the Scotchmans, the granite surfaced only in a few places. Broken, angular, ragged, rotten sediments passing for rock still dominate today the makeup of these mountains. As Nan Compton says, after having seen a video of the Scotchmans taken from a plane, “I had no idea the area was so rugged and wild. From Little Spar Lake to Scotchman No. 2 is one huge mass of cirques and slide areas, boulders bigger than houses, mountain meadows and animal trails. Sawtooth sticks up like a huge nose with Middle Mountain between it and Clayton Peak.”

The continental ice sheet from the north did its best to soften the edges of the Scotchmans, but the massive glacier’s leading edge halted its southern progress at the mouth of what we now call the Clark Fork River and created an ice dam more than 2,000 feet thick. This is what created Lake Missoula, a lake that ate away at the edges of the ice from Pillick Ridge to the Missions, the Rattlesnake and the Sapphires. And it ate away at the ice dam itself so that finally, and maybe many times over, the dam collapsed and the lake catastrophically drained into Idaho and Washington, carrying Montana sediment and boulders all the way to Oregon.

The Scotchmans, site of the wondrous ice dam that created such havoc to so much of the Inland Northwest, watched all this happen, then spent the next 10,000 years evolving the forests and wildlife found there today.

Scotchman Peaks The Landscape

A little-known chunk of wild country occupies a place in the Cabinet Mountains where the Idaho-Montana state line slices through the mountains north of the Clark Fork River. Bounded by Lightning Creek in Idaho and Bull River in Montana, the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area is comprised of 88,000 acres of undeveloped public lands managed by the Idaho Panhandle National Forests and the Kootenai National Forest. Much of this rugged landscape is as inaccessible now as it was almost 200 years ago when David Thompson explored the Clark Fork River and established a trading post at nearby Lake Pend Oreille.

Among the reasons why the area remains so wild is the ruggedness that characterizes so much of its terrain. Crowned by Scotchman Peak at 7,009 feet, the highest point in Bonner County, Idaho, the heart of the Scotchmans is defined by two sheer ridgelines separating Lightning Creek from Blue Creek and Blue Creek from Ross Creek, the primary drainages bisecting these mountains. This remote high country boasts glacially carved basins with exposed sedimentary rock hundreds of millions of years old.

More than 40 streams from Mink Creek to Gin Gulch tumble off two-dozen named peaks stretching from Lightning Mountain to Pillick Ridge. A great deal of water is shed by the Scotchmans, yet despite the liquid abundance, there are only three or four lakes within the roadless area, and only one of those has a name: Little Spar Lake.

The water flowing from the Scotchmans goes in two directions, but ultimately ends up in the same place. Ross Creek, Spar Creek and Keeler Creek with their tributaries all flow into Lake Creek, which meanders north from Bull Lake to the Kootenai River. Bull River, Blue Creek and Lightning Creek, with their 30 or more tributaries, flow into the Clark Fork River, which empties into Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho’s largest lake.

Several small communities are located in the vicinity of the Scotchmans. Clark Fork, Idaho, is situated at the confluence of Lightning Creek with the Clark Fork River; Heron, Montana, is on the south bank of the Clark Fork about halfway between Blue Creek and Bull River; Noxon, Montana, is five miles southeast of Bull River; and Troy, Montana, is a dozen miles north of Bull Lake where Lake Creek joins the Kootenai. Access to the Scotchman Peaks Primitive Area begins in these communities. Highway 200 parallels the southern edge through Idaho and Montana. At Clark Fork, Idaho, Lightning Creek Road No. 419 follows Lightning Creek all the way to Rattle Creek. Here a U.S. Forest Service Road climbs over Rattle Pass and descends Keeler Creek, eventually joining Lake Creek Road No. 384, which exits the mountains to Troy, Montana, and Highway 2. Highway 2 is connected with Highway 200 in Montana by way of Highway 56, commonly called the Bull River Highway, which is often lauded as the most scenic drive in western Montana. From this road there is vehicle access to Spar Lake and the Ross Creek Cedars.

A small but well-maintained trail system provides exceptional hiking opportunities into the Scotchmans. The most heavily used trails go to Little Spar Lake, Scotchman Peak and Star Peak, where an active forest fire lookout tower is manned during the summer months. Approximately 50 to 60 miles of foot trails probe the backcountry of the Scotchman Peaks.

Geology, Ice and Water

The Scotchman Peaks are an historic mountain range. David Thompson saw them much as they are today when he passed this way in 1809. But travel further back in time – like say 12,000 years – and you would not have recognized this place. It was covered in ice and water. Glacial Lake Missoula, that gargantuan body of water that contained more liquid than all the rivers of the world today, lapped at icy shorelines more than halfway up the sides of Star Peak and Clayton Peak, and totally submerged Fatman Mountain. Arctic conditions ruled the landscape in those days.

But go further back in time still, through thousands of centuries and hundreds of millennia, and you will enter a region covered by a vast sea. The Scotchmans, as is most of the Cabinet Mountain Range, is sedimentary in origin, which means the layers of mud and silt and sand that mark each horizon of rock were laid down over countless millions of years by the simple mechanics of erosion and deposition. And then the earth trembled, buckled and moved, heaving upward into the sky, and the sea vanished. The mountains were born, a rugged range of fractured slabs of lake bottom silts metamorphosed into rock.

When these mountains were already ancient, another period of violent activity within the earth’s crust pushed sills of granite and diorite into the spaces between the sedimentary layers. This was up to135 million years ago. To the west, the Selkirk Mountains came into being, but in the Cabinets and the Scotchmans, the granite surfaced only in a few places. Broken, angular, ragged, rotten sediments passing for rock still dominate today the makeup of these mountains. As Nan Compton says, after having seen a video of the Scotchmans taken from a plane, “I had no idea the area was so rugged and wild. From Little Spar Lake to Scotchman No. 2 is one huge mass of cirques and slide areas, boulders bigger than houses, mountain meadows and animal trails. Sawtooth sticks up like a huge nose with Middle Mountain between it and Clayton Peak.”

The continental ice sheet from the north did its best to soften the edges of the Scotchmans, but the massive glacier’s leading edge halted its southern progress at the mouth of what we now call the Clark Fork River and created an ice dam more than 2,000 feet thick. This is what created Lake Missoula, a lake that ate away at the edges of the ice from Pillick Ridge to the Missions, the Rattlesnake and the Sapphires. And it ate away at the ice dam itself so that finally, and maybe many times over, the dam collapsed and the lake catastrophically drained into Idaho and Washington, carrying Montana sediment and boulders all the way to Oregon.

The Scotchmans, site of the wondrous ice dam that created such havoc to so much of the Inland Northwest, watched all this happen, then spent the next 10,000 years evolving the forests and wildlife found there today.

Links to Route Descriptions

PHOTO GALLERY

Click to set custom HTML